All good family’s (houses)

MaryAnn Taylor

are (not)

похож

The story of the Little House Quilting Club (LHQC) is a bittersweet work of art patchworked together with painstaking love. In addition to quilting, Marianne Hales is single-parenting two kids, Emily Laura and Micah, caring for her aging parents, teaching college courses, and courageously battling Multiple Sclerosis. It seems unimaginable that she finds the time for anything else, but creativity seems to pour from her veins. She explains that, aside from monthly massages, and half an hour of mindful meditation each morning, textile art is her self-care. Over the past thirteen years, Marianne has designed and completed seven quilts. She’s set up a felt-covered idea board in her sewing room that serves as her canvas from which each quilt germinates.

“It takes time to let the ideas percolate,” she explained. “It can take me years to finish a quilt because I just do it a little at a time. If I sat down and did it full-time I could do it very quickly, but I need to think about how I want it to be; then I’ll draw it out, erase, draw it out and erase. It can easily take up to six months to come up with a finished design. I’ve easily been working on these two latest quilts for five years. And when I finish something, I’m planning ahead for what I’m going to do next.”

Hence, the eight-year development of her LHQC quilt (which Marianne considers a textile chapbook, or small book of poems), and its journey toward completion.

“I met Chelsi Linderman in 2010, when we both adjuncted at Dixie State College. Her husband, Trevor, had been diagnosed with brain cancer in his teens, and given a prognosis of ten to fifteen years.”

Four years later, both Marianne and Chelsi had moved to Springville, Utah. In December 2014, after six years in remission, Trevor’s cancer returned. Chelsi, in need of community, reached out to a number of women she considered friends, and they organized a club.

“In the beginning there were ten to twelve of us. We swapped fabric, and began working off the same house block pattern to make individual quilts,” said Marianne.

It soon became apparent that Trevor was in the last stage of his illness, and the club rallied around Chelsi. They met monthly to share brunch and their love for textile art. A few of the women each pieced an individual house block for a second quilt to commemorate Trevor’s life. He died in May 2015. Marianne and her new friends continued to support Chelsi through the following year until the club ended in spring of 2016.

As the women parted, Marianne penned a poem in homage to their sisterhood.

Little House Quilting Club

We swapped fabric and stories

over french toast casserole,

once a month for about a year:

pieces of a star that only met

at one point, strangers

trying to bind up the grief

of one little house with scraps

and thread from our own.

Paper piecing is an act of faith

counter-intuitive seams fold

into the expected unexpected

with centimeters of stitches

filling ten rows across

and ten rows down;

ninety blocks later it’s still

a surprise when it works

(and when it doesn’t).

Funny how different

blocks can be made

from the same patterns,

two walls, one door, one

window, one roof, two

chimneys, anonymous

little houses painting

the same shape of lives

in endless color combinations.

No hint of the ordinary sorrow

underneath, uniform

batting adding dimension

to grief that doesn’t follow

a template: lean in, move

on, get out of bed or don’t—

ninety months later it’s still

a surprise when it knocks

you down (and when it doesn’t).

The club faded away after

the long-anticipated funeral

changed the pattern

of daily life, but never

did disband: this quilt

was finished and others

were waiting. There will always

be another kitchen, another

brunch, another stitch.

“We began as strangers,” said Marianne. “And we were brought together by the quilt. Even after the club ended we remained close.”

In 2017, Marianne started a third quilt, smaller than the others, but built on the same house-block pattern as the previous two made by the club. She stitched her poem in five individual blocks, and began piecing together tiny houses from the fabric originally swapped by members of the club. Marianne’s ideas for the LHQC quilt came together as the world was met with Covid-19, and she penned a second poem:

Pandemic Epiphragm, Spring 2020

When you go outside

at the same time as your neighbor

nod to acknowledge

your common humanity and pretend

your box kingdom

is self-contained and self-sustaining

not one in a row of square foot human gardens

connected at the seam and color-coordinated

walls and carpets and windows that see

the sun high and low and gone

grass that must be wrangled

two bright green rocking chairs

with pink flamingo cushions

sidewalk cracks painted with weeds

your neighbor’s daughter’s boyfriend’s

walk around the block, spend the days

calming your panic

move from the back yard to the front

with the sun, close your eyes

for a few minutes when the sky is navy

push down the dread of light blue

you have your box Kingdom.

A snail has crawled up

the foundation and closed

its opening with a mucus epiphragm

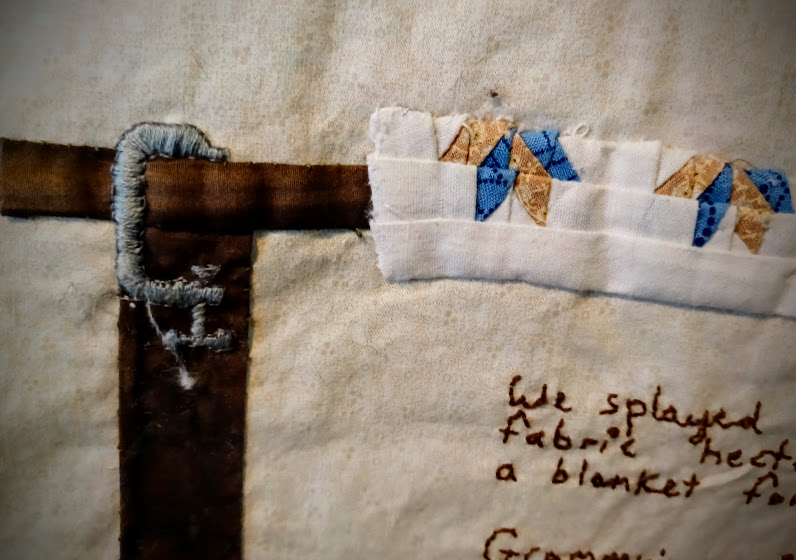

Marianne, inspired to draw her people together, reached out to her community of writers—Provo Poetry. She sent out a call for poems about quilting, and Steven Duncan, of SFYS open mic and Rock Canyon Poets, responded with memories of a childhood he spent hiding under quilting frames:

We splayed under the canopy of

fabric hectares rolling wide and warm,

a blanket fort under construction.

Grammie’s voice was a sprinkler

we loved to run through in summer

over and over, and overhead

her stitching brought together

the endless scraps and gathered folds

with every single piece of us.

Marianne stitched his poem into yet another block, and then carefully adorned it with a tiny pieced quilt stretched across an embroidered frame. She took up the task of needle-and-threading her way through her homage to the club, and their recipe for the monthly brunch.

Here’s What’s Cooking: French Toast Casserole

From the kitchen of Mr. Food.com and Debbie Hong

14-16 slices hearty white bread

(about 10 cups of 1 inch cubes)

1 (8 ounce) pkg cream cheese

8 large eggs 1 ½ cups milk

2 ½ cups half-and-half ½ cup maple syrup

1 teasp vanilla 2 tablespoons confectioner’s sugar

Coat a 9×13 baking dish with cooking spray

Place bread cubes in baking dish Beat cream

cheese until smooth. Add eggs, beating after each

addition. Add milk, half-and-half, maple syrup,

and vanilla. Mix until smooth. Pour cream cheese

mixture on top of bread cubes. Cover and chill

for at least two hours, or as long as over night.

Preheat oven to 375°. Let dish stand at room

temp for 20 minutes. Bake 45-60 minutes or until

set. Sprinkle with confectioner’s sugar.

This, her fourth and final quilt, accompanies the third, and serves as a poetic story describing the comradery and purpose behind Chelsi’s club. The quilt tells the story of Marianne’s love for her community and her devoted service to the people she houses in her heart. It is nothing less than a work of art. Upon their completion, Marianne enters each of her quilts in the annual show sponsored by Springville Museum of Art, and then passes them on as gifts to friends and family members.

Marianne Hales is a poet, essayist, and playwright living in Springville, Utah. She has been published in Dialogue: a Journal of Mormon Thought, Segullah, The Hong Kong Review, Helicon West, and Rocky Mountain Runners. Her plays have been produced across the U.S., and adapted for film. She teaches at both Brigham Young University and Western Governors University. In 2015, she co-founded Provo Poetry, a non-profit dedicated to bringing poetry into the community at large in unusual ways. That same year she spearheaded Speak for Yourself, a weekly creative writing open mic, which, since the pandemic, meets face-to-face at Enliten Bakery once a month. Marianne is a member of the Rock Canyon Poets, a longtime fan and contributor to the MoLitBlitz, and a member of the inaugural cohort of the MoLitLab’s book mentorship program. Additionally, she is Head Curator for the Plein Air Word Gallery; a rotating display of laminated poetry on the fence outside of her house. She is presently revisiting her early diaries, reading them aloud to her kids so as to illustrate that she, too, was also once a hormonal teen.